These previously unpublished photographs of the Home Guard offer a rare candid view of an often-overlooked part of New Zealand’s experience during the Second World War. Far from being a safe sideshow, with limited resources these men bravely faced a genuine threat and were prepared to defend their homeland against enemy invasion.

I found these original snapshots in a second-hand bookshop. As a hobby, I collect orphaned photographs like these and research the stories behind them. One of the most striking of the photographs in this series shows a teenage boy in full uniform with a rifle slung over his shoulder.

Braithwaite, a young member of No. 12 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, 1942. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

We are used to seeing images of fresh-faced boys from the Hitler Youth fighting among the ruins of Berlin, but it seems even more jarring to see such a young Kiwi lad prepared to defend the hills behind Wellington, New Zealand. Who were the Home Guard? What were they doing at Makara? This is their story.

The sleepy settlement at Makara Beach is 16 kilometres northwest of Wellington, where steep hills and cliffs flank a stony beach. This is an inhospitable coastline with jagged rocks and little protection from the notorious northerly winds. The foreshore still bears evidence of a settlement of Italian fishermen, but that’s another tale. Further up the hills, the remains of a Māori Pa can be seen. This is an area steeped in history.

It is difficult to write about the Home Guard without paying homage to the iconic BBC series, ‘Dad’s Army’, where a motley crew of misfits defiantly stood as England’s last line of defence against Nazi Germany. When people think of the Home Guard it is often that image that comes to mind.

Four members of No. 11 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, taking a break at Makara, 1942. From L to R they are Elice, Maris, Lieutenant Richards and smoking the pipe is Sergeant Milwood. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

The formation of New Zealand’s Home Guard in 1940 was directly inspired by their well-known British equivalent. The Wellington coastline was about as far away as you could get from Nazi Germany, but that didn’t stop enthusiastic volunteers from signing up to defend these shores – just in case. In fact, unknown to the new recruits, there actually were genuine threats approaching New Zealand waters – German surface raiders were on the hunt in the South Pacific. They laid a minefield off the Hauraki Gulf, which sank two vessels, and later also laid minefields at the entrances of both Wellington and Lyttelton. They also sank the Turakina in the Tasman Sea, and captured and sank the Holmwood off the Chatham Islands and the passenger liner Rangitane three days out from Auckland.

There were some people who feared that one of these German raiders might pose a direct threat to the capital. At a St. John meeting in February 1941, Wellington’s Mayor, T. Hislop, gave the following warning:

“If you had a raider – just one – lying off here, not necessarily at Lyall Bay where it might have to deal with Fort Dorset, but off Makara, it could easily send in shells over the hills. A ship with eight guns would fire, depending upon the calibre, about 20 shells a minute – about 1200 in an hour. So, a quick raid of only an hour can land, with reasonable marksmanship, 1200 shells in this place.”

The sinking of ships in New Zealand waters certainly brought the war a lot closer to home – and perhaps it encouraged some men to do their bit by joining the Home Guard, but the imagined scenario of a German raider approaching Makara to stealthily fire shells over the hills seems far-fetched and of course never happened – the raiders were here to disrupt shipping and didn’t want to give away their presence and risk retaliation.

On 30 November 1941, the Makara Battalion of the Home Guard, made up of the Karori, Northland, Kelburn, Ohariu Valley and Makara units, celebrated their first birthday with a march from Kelburn to Karori Park, where none other than Prime Minister Peter Fraser was waiting to inspect their parade. He congratulated them on their discipline and numbers, acknowledging that the Home Guard was no “side show” and that more arms and uniforms would be provided to them as soon as possible. He also warned that they might soon have to deal with another threat that was looming over the horizon:

“At the present moment everybody can see that there is a very critical situation in the Far East, in the Pacific, in that part of the world where we are,” he said, and added that if the situation in the Pacific developed more ominously it would be something for those guiding the destinies of the country to feel and know that the people were responding to the call and playing their part.”

Evening Post, Volume CXXXII, Issue 132, 1 December 1941

Prime Minister Peter Fraser addressing the Makara Battalion of the Home Guard and Women’s War Service Auxiliary and Red Cross units at Karori Park, 30 November 1941. Evening Post, Volume CXXXII, Issue 132, 1 December 1941, courtesy of Papers Past

If only Prime Minister Fraser knew just how prophetic his words were; on the following Sunday his feared ominous development occurred – the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. New Zealand was no longer safe. The Makara Home Guard had to prepare for the unthinkable – the possibility of an enemy invasion.

Soon the Home Guardsmen were hard at work at Makara Beach, digging defensive gun emplacements and trenches. During the summer months, New Zealand’s beaches are usually the domain of holidaymakers and sand castles, but through the summer of 1941/2 they had to make way for barbed wire and other anti-invasion measures. Occasionally the tension between civilians and military forces resulted in scandal, as was the case on one heated occasion at Makara.

“A DISGUSTING EXHIBITION”

“Complaints that a number of men of the Makara Battalion, Home Guard, went in for a bathe without clothing of any kind in the presence of women and children at a beach in the Wellington district last Sunday have been received from residents by the chairman of the Makara County Council Mr. J. Purchase.”

“Mr. Purchase said yesterday that it had been reported to him that late on Sunday afternoon men of the battalion decided to go for a swim, and though several had no bathing suits they stripped off in the full view of women and children who were bathing there and entered the water. The men ignored protests by bystanders and the women who were present.”

“Some time ago, he continued, the Makara County Council made the men’s bathing shed at this particular beach available to the Home Guardsmen, but on Sunday they made no attempt to use the shed. There were girls present from 16 to five years of age, and when these turned away in disgust the men deliberately confronted them, remarking that civilians had no right to be on the beach.”

“It was a disgusting exhibition and one that should be strongly dealt with by the military authorities.”, declared Mr. Purchase.”

“The officer commanding the Makara Battalion, Home Guard, to whom the statements of Mr. Purchase were referred before publication, said that it was possible that a few men might have bathed naked in the sea, but most of those who did bathe improvised suitable costumes. The men had been digging all Sunday, when there was a mean maximum temperature of 73 degrees in the shade, and it was not unnatural that some desired to cool themselves. Had not a number of civilians persisted in remaining in the vicinity of defence works there would have been no cause for complaint.”

Auckland Star, 31 January 1942

Some of my photographs show members of the Home Guard hard at work digging defences; sometimes with their shirts off, suggesting that they were working in the hot summer sun. I wonder if perhaps some of these men are the ones responsible for the scandalous skinny-dipping incident. They are laughing about something. Maybe one or more of these photos were even taken on that very day.

Members of No. 10 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, hard at work digging defensive positions at Ohariu Bay in 1942. From L to R, they are McDermott, Sheilds, Brawn, Pike, Bell-Harry and Thompson. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

Members of No. 11 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, digging defensive positions at Ohariu Bay, Makara, 1942. From L to R they are Fowler, Yates, Leighton (front), Stewart (back), Hall, Rhodes (front), Welsh, Pine and Button. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

Members of No. 11 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, digging defensive positions at Ohariu Bay, Makara, 1942. They are, L to R, Fromer(?), Rhodes (back), Lipson (front, Fowler (back), Hall, Yates (back), Bridge (middle), Hertzfield (front) and Pine. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

In February, the Japanese captured the British stronghold of Singapore and also bombed Darwin. It seemed that their expansion through the Pacific was unstoppable. To make matters even worse – the prime of New Zealand’s armed forces were on the other side of the world locked in the struggle with Nazi Germany. It is hard for most of us to imagine what it must be like to face the possibility of an enemy invasion – but that is the reality that New Zealanders faced in 1942. All of these photographs of the Makara Battalion of the Home Guard were taken during that year – although in most instances the exact dates aren’t recorded.

The surnames of some of the guardsmen are written on the back of the photos – I’ve noted these where that is the case. If you recognise any of the names or faces and would like copies of these images then please let me know.

An overexposed photo of the cooks of C Company, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, at Makara, 1942. They are L to R, Bryce, Casper, Kelly, Stewart and Cher(?). Lemuel Lyes Collection.

Members of the Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, take a break in the hills above Ohariu Bay, Makara, 1942. They are, L to R, Fowler, Bridge, Butt, Welsh, Milwood, Hall, Elice, Rhodes (above) and Hertzfield (below). Several of the men are wearing their Home Guard armbands – an example of which, from a member of the Makara Battalion, survives at the National Army Museum Te Mata Toa. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

The Home Guardsmen’s work at Makara Beach included removing two-metre high sand dunes to prevent their use as cover during any Japanese landing. They also constructed some concrete-lined trenches; the remains of some can still be seen today. One of the photographs in my collection shows what might be a similar trench at Te Ika-a Maru Bay. High in the hills above, two six-inch guns were installed at Fort Opau.

Possible trench at Te Ika-a Maru Bay, 1942. Unfortunately, someone has attempted to colour this photograph. They weren’t very good. I’m sharing this anyway in case it might inspire someone to go look for the trench. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

A large number of Home Guardsmen were veterans of the First World War, too old to serve overseas again but not the geriatrics that one might imagine – many were in their forties and fifties – they were husbands, fathers, business owners, farmers and labourers.

Mr. Stewart (Our Cook), No. 11 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard at Makara, Ohariu Bay, 1942. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

Initially, they were volunteers, but in 1942 compulsory service was introduced for those between the ages of 35 and 50. Alongside them were teenagers; too young to join the armed services but still keen to do their bit for the war effort. Many of these youngsters already knew how to handle firearms and had picked up other useful skills in Boy Scout troops or Cadet units. In the event of invasion, the men and boys of the Home Guard were willing – if necessary – to do whatever it took to defend Wellington; they would’ve been outgunned, outnumbered and without adequate air cover, but they were prepared to stand and fight.

The same spot today. Thanks to the owner who kindly let me go exploring in their backyard. © Lemuel Lyes

Some of the Makara Battalion prepared not only for the first response to any attack but to then also fight a guerrilla war behind enemy lines. A special ‘Guide Platoon’ was formed with men that knew every gully and ravine in these hills and planned to make the most of that advantage. They even planned to use disused mine shafts (from the often forgotten gold rush on Wellington’s doorstep – yes, that’s another story too) as hiding places and supply depots. This guerrilla unit was largely the brainchild of Lieutenant Harold ‘Pip’ Bollard, a solicitor and former member of the Victoria University hockey team.

One of the Makara Home Guard’s most ambitious exercises was a dress rehearsal of the expected invasion. On 23 August 1942, one company of men were to play the part of the Japanese and make an attack somewhere on the coast between Te Ika-a Maru Bay and Sinclair Head. Two other companies wearing white armbands were tasked with defending that area – with no prior knowledge of exactly where to expect the attack. During this exercise, the defenders had one key advantage – air supremacy. A lone RNZAF Tiger Moth from Rongotai Air Station was to act as aerial reconnaissance; and in the passenger seat was none other than Lieutenant Bollard, chosen due to his excellent knowledge of the terrain. After spotting the ‘enemy’ and reporting their position, the Tiger Moth was to slow their progress by dive-bombing them.

The exercise area was split into six parts. The Tiger Moth was tasked with searching a sub-area and then flying over the defenders’ headquarters at Karori West Park, where it was to communicate with the ground by circling the same number of times as the number of the sub-area and then waggling its wings if the enemy had been spotted. They were then to drop a written note confirming their observations.

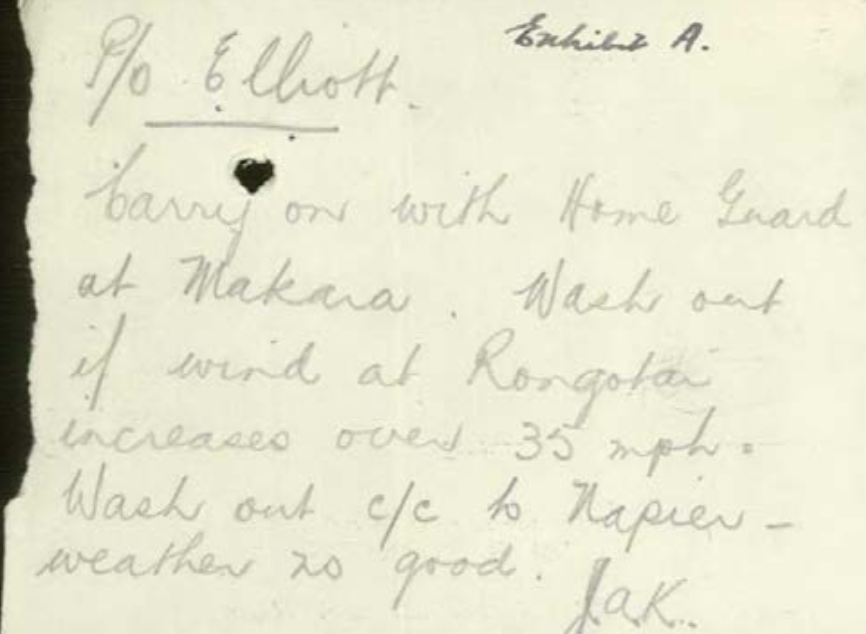

The day before the exercise, Flying Officer John Kirkcaldie, Officer Commanding, No. 2. Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Flight, briefed Pilot Officer Elliott on the task he was to perform for the Home Guard. At 0800 on Sunday, 23 August 1942, the two were to meet at the aerodrome so Kirkcaldie could give his final instructions, but Elliott didn’t show up. Instead, Kirkcaldie, who had to leave for Gisborne, left a written note for Elliott in the Authorisation Book, for him to read when he signed it before take-off. It advised him to cancel the flight if winds reached over 35 miles per hour.

At 0900 hours the exercise began. Somewhere in the hills behind Wellington, an invasion took place and a company of Home Guardsmen started moving inland. At the same time, over at Rongotai Aerodrome, the Tiger Moth was supposed to be taking off – but there was still no sign of Pilot Officer Elliott. Lieutenant Bollard waited patiently until 0945 hours when a taxi arrived at the aerodrome and Elliott emerged, hurriedly dressed, and finally, the Tiger Moth took off, heading westward to spot the ‘enemy’.

At 1010 hours they circled the park once, instead of twice, and dropped a message that simply read “NO SIGN AREA 2. ITS BLOODY ROUGH BELIVE ME.” The Tiger Moth then headed in a south-easterly direction. The next sub-area it was to search was No. 6. The Tiger Moth was seen and heard by several witnesses over the next 50 minutes but there were no more messages delivered to Karori Park. At 1120 hours Captain Wheely phoned Rongotai to find out if the plane had landed. It had not.

What started as an invasion exercise quickly turned into a search and rescue operation. At 1500 hours hundreds of Home Guardsmen were sent out across the exercise area, with many staying in the field overnight and continuing the search the following day. There were further ground searches through until 28 August, and then again on 30 August. Aerial searches were conducted by the RNZAF, covering not just the immediate area of the exercise but also as far north as Kapiti Island, but sadly there was no trace of the missing aircraft. The search was abandoned and the next of kin advised that they shouldn’t hold out hope any longer.

The Court of Inquiry found that the cause of the accident was an error of judgement on the part of the pilot in continuing the exercise in adverse weather. He hadn’t signed the Authorisation Book before take-off, so never received the note left by his commanding officer advising him to cancel the flight if the wind was over 35 mph. Reports indicate that the wind was between 30 and 40 miles per hour on the ground and between 35 and 50 miles per hour further up.

The loss of Lieutenant Bollard was a terrible blow not just for his family but also for the close-knit men of the Makara Battalion. On 6 September 1942, they attended a memorial service for him at St Mary’s Church, Karori. During the service, Rev. Kempthorne said, “As a Home Guardsmen, Lieutenant Bollard had done his part in the cause of freedom and liberty just as much as those who had gone to the fields of battle overseas.”

As the year progressed, the threat of Japanese invasion slowly faded away. The Battle of the Coral Sea stalled them and the Battle of Midway shifted the balance of power in the Pacific. There was an invasion of Wellington, but thankfully it was the Americans and not the Japanese. By the end of the year, it was obvious to most New Zealanders that the direct threat of an enemy invasion had passed. One of the last images in this series of photographs shows C Company of the Makara Home Guard on parade at 8:30 a.m. on Christmas Day at Te Ika-a Maru Bay.

Members of C Company, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard, on parade at Te Ika-a Maru Bay, 8:30 a.m., Christmas Day, 1942. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

By the end of the following year, the orders came to start the process of removing all the barbed wire and refilling all the trenches that they had spent the previous years digging. Summer was on its way and Wellingtonians wanted their beaches back.

In 1945, as the war drew to a close, the Makara Home Guard continued to hold regular gatherings; sometimes hosting military speakers, exhibiting films on the war effort or putting on entertainment for the public. Then on 21 June, a discovery was made in a gully in the vicinity of Te Marama Station. A nineteen-year-old farmhand had climbed down a bank to find out why his dog was barking and refusing to heel. The missing Tiger Moth had been found at last.

“In view of the turbulent air conditions arising from the strong gusty north westerly wind and the hilly nature of the country it is considered likely that while proceeding up the gully in which the accident occurred the pilot encountered down draught conditions which forced him into a position in which there was insufficient room to carry out any manoeuvre other than attempt to climb out of the gully against the down wind. The fact that the aircraft flew into rising ground up the gully approximately into the wind and hit at a shallow flight angle is considered to support this theory.”

‘Accident Involving Aircraft NZ1432, Memorandum for The Honourable Minister of Defence, 27 June, 1945’. RNZAF Accident Reports – DH 82 – NZ 1432. Archives NZ

The remains of the two men were recovered – and they were finally given a proper burial. The Makara Home Guard again turned out to support Bollard’s family and to pay respect to their fallen comrade. Pilot Officer Elliott was also given a final farewell.

On 15 August, New Zealanders celebrated the announcement that Japan had surrendered. The long and bloody war for the Pacific had been won. Two months later, Wellington Fortress Commander, Colonel L. W. Andrew, V.C, addressed the men of the Makara Battalion one last time.

“Some of us wondered what might have happened had the Japanese attempted to land in New Zealand. Well – it would have been a nasty mess, but it would also have been a grim fight….In operating in your area, with its many hills, you showed the value of the training to which you had given keen attention. Your standard of fitness compared more than favourably with that of the territorial battalions. I look back with pride upon my short period with Fortress Command, and I think that we were producing something when the balloon went down… It is wonderful to look back upon those fortunate – or unfortunate-days of service, just as it is to see you men here together in a really democratic spirit. You joined in a spirit of helpfulness and you worked in together all the way. Keep it up, gentlemen! We need it in this country.”

18 October 1945, Evening Post

No. 12 Platoon, Makara Battalion, New Zealand Home Guard at Makara, 1942. If the Japanese had invaded then these are some of the men that would’ve defended Wellington. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

Makara Beach hasn’t changed too much since that summer when the Home Guard furiously dug trenches and prepared for an invasion that thankfully never came. The sand dunes are still gone, the hills are still steep, there is even still some evidence of the trenches, although most have long since been filled in. Now there are turbines along the tops of the hills, harvesting the power of the notorious wind. There is a lovely café – and it is still a great place to enjoy a stroll along the beach. So, if you are looking for somewhere near Wellington to explore then perhaps consider a trip over to Makara Beach, where you can enjoy the windswept beauty and at the same time remember the boys and men that were willing to make a stand here in defence of our capital. Skinny-dipping is still frowned upon.

View looking north from Fisherman’s Bay, Makara in 1942. A time when the Japanese threatened to arrive over the horizon. Taken by a member of the Makara Home Guard. Lemuel Lyes Collection.

The same view today, looking north from Fisherman’s Bay, Makara Beach. Little has changed along this coastline. © Lemuel Lyes

If you’d like to read more about the activities of the Home Guard at Makara then I highly recommend ‘The Makara Guerrillas’ by Greville Wiggs in ‘The Stockade’ Issue Number 29, and the excellent biographical book ‘Ghosts of Makara’ by Bernard Diederich. To learn more about the Home Guard and the coastal fortifications of New Zealand I recommend ‘Defending New Zealand – Ramparts on the Sea 1840-1950s’ by Peter Cooke. All of the above were referred to during research for this article, as were the Archives New Zealand file on NZ1432 and numerous newspaper articles courtesy of Papers Past. I’d like to thank Doug Dillaman for joining me on the field trip to Makara Beach, and also the kind locals who helped me find some of the spots where the original photographs were taken.

Lastly, I’d like to dedicate this article to my Gramps, who passed away last year at his home in Wellington. As a teenager, he served with the Home Guard in Taranaki and I greatly miss hearing him tell stories from those distant days.

© Lemuel Lyes

Categories: Second World War, Wellington

I knew New Zealand felt they were in danger of Japan’s huge growth spurt, but for some reason I never heard anything about the Home Guard. I feel rather ignorant at the moment for not knowing. You have given these photographs a good home and have made certain their history was included. Thank you for being so thorough, Lemuel, and i will look into those books.

No need to feel ignorant, even here in New Zealand the Home Guard often only appear as a brief footnote in regional history books. Peter Cooke’s book is a notable exception. The Makara unit was just one of many HG battalions up and down the country – and I expect that they all have their own stories waiting to be told. Hopefully there are also more photos waiting to be discovered!

I know you’ll do your best to save them.

I’d be wary of Cooke’s book as a resource. It’s a useful one-stop collation of data he’s copied across from various places but he’s made mistakes in the process. A friend of mine took Cooke on over some of his errors a little while ago,.

Thanks for the heads-up, that’s really good to know. In an ideal world I’d like to be able to refer to the original records at Archives NZ more often – but due to my location and budget I can’t do that as often as I’d like. While researching this post I ordered a scan of the RNZAF Accident Report, which was extremely useful, but I wish that I could’ve had access to other files as well!

Your meticulous research and accompanying photographs pull together a number of threads from this era, of circumstances gallant, humorous and poignant. Thank you for this most interesting and touching article.

Thank you very much! I’m sure that every HG unit up and down the country had similar stories. It was a privilege to research this article and I hope that it inspires others to look into the history of the HG in their own hometowns – and especially to talk to any parents or grandparents who may have served.

Excellent thanks Lemuel.CheersSuzanne

Sent from Yahoo7 Mail on Android

Thank you!

Such a thrilling, well-researched story! I was laughing so hard at Pilot Officer Elliott’s antics until I read the tragic end. I bet New Zealand never really hears war stories about the home front. This is as good as it gets!

Thanks, Jack! Yes, it really is tragic what happened. It was a sad reality, especially in aviation at that time, that not all casualties of war were on the front lines. If he had got the note then he probably would’ve called the mission off, but then again, it was touch and go with conflicting reports of exactly what the wind strength was, and he did have experience flying in those conditions (as would most pilots based in Wellington).

A great tribute to gramps Lemuel.He would have chuckled at the story you have brilliantly researched her, and then given you a few more.is there someway this could be published in the dom post?

Yes, he would’ve enjoyed it! I actually got to share the photos with him during one of my last visits, which of course led to another chat about his experiences in the HG. He would’ve been about the same age as the lad in the photo at the top.

Its my understanding that the engine from the Tiger moth was recovered by locals (60s or 70s) and was for a time at the Makara garage – whats left (if any thing) of the plane is still in a bush glad gully on the hillside up behind the northern end of the the Makara 18 hole Golf course on Terawhiti Station. I heard that it caught fire, if so litte would have remained but enough did survive to warrant recovery of the engine.

I also understand that in a gully behind the Makara school is the remains of a Home Guard supply dump – It was last seen I believe in the 1970s approx by a local who’s Dad took them up to see it ! – Remains of a wooden door and wall across the front of an old mine shaft I understand.

I personally havent seen it – even though the general location has been pointed out – as it is likley to be in a difficult steep location overgrown with gorse etc – difficult to see from many angles.

That is great information, thanks for sharing! I had wondered if the engine had ever been recovered.

You are right – according to the official Archives NZ file on the crash, the fuselage, wing and control surface coverings had been totally destroyed by fire and the wooden structure badly charred. Due to the hilly and rocky terrain it wasn’t possible to bury all the remains of the airframe, but it was broken up and placed out of sight among trees above the creek bed.

The engine was relatively intact, but in 1945 the air force deemed that it was too difficult to carry it out – so it was partially dismantled – and during that process it was found that it had corroded anyway. It was broken up and buried next to the creek bed.

So perhaps something remains of the crash site if someone was determined enough to find it and knew what to look for. I’d be curious to find out where the engine ended up – it must’ve taken considerable effort to carry it out!

That supply depot sounds extremely interesting! I’d love to hear from anyone who manages to find it. I wonder what is left of it…

Thanks again for sharing this information.

My understanding was it was removed for the intention of further use – in another life – but I couldnt confirm if that ever happened. Perhaps it wasnt as badly broken up as the report indicated.

We also want to find the old hutt duimp but have never been keen enough to push around the gorse and scrub or had the time when walking in the gully area.

Dear Lemuel,

Thank you very much for your work in putting together this article. I appreciate the time and effort that research like this involves.

Yours sincerely

Christopher

________________________________

Hi Christopher. Thank you very much for the kind words! It certainly takes considerable time, but it is always an absolute pleasure to learn more about our past and to share it with others. I just wish I had the time to research every Home Guard unit, as I expect that they all have important stories to tell. Thanks again for stopping by. Kind Regards, Lemuel

Excellent post Lemuel. Well researched and a topic I was not really familiar with. I read and saw some of the defensive structures build in Auckland, but was unaware of these sites in Wellington. It is indeed a tragic story about the Pilot and passenger and I wish they would have returned. I am also very pleased to see that you preserved these photographs (and digitized them) for future use. It surprises me all the time to find such photos (or private photos from the 70s and 80s seemingly discarded in a shop (or even worse in a dumpster). Always makes me sad to think that whoever had them in their possession passed away without being able to give them to someone that would treasure them.

Anyhow, thank you again for all the effort you put into this post!

Thank you very much! I’ve always been fascinated by surviving examples of coastal defences around the country – I spent many a holiday exploring them around Wellington and there are actually quite a few that survive. There is Fort Opua in the hills above Makara, then the big battery on Wrights Hill. The observation post at Moa Point was a favourite of mine when I was younger – and I still look out for it whenever I fly into Wellington airport. Godley Head at Lyttelton is one of my favourites in NZ. On the other hand there is very little that survives from the HG.

I agree – it really is sad to think about how many invaluable historical records end up in landfills every week. I suspect many people simply don’t realise the historical value. The best case scenario is that the family donate them to a local museum, library and archive – along with all of the background information. I try to do what I can to ‘rescue’ any orphaned images like these that I come across, and of course share them, but by that point they are usually stripped of any context.

A great post – some wonderful photos. It’s amazing how much ‘unseen’ NZ history is out there. Makara always was the lynch-pin of Wellington’s defence during the war, particularly once the fort was operational – between that and the AA batteries on Somes Island they had the place fairly well covered. We forget that we had a Home Guard! The threat from Japan was regarded as palpable by the government well before war broke out – anything from invasion to large-scale raids – and there was also the risk of landing parties from German auxiliary cruisers or U-boats. In the end, of course, just one German U-boat ever visited, and that right at the end of the war, but the government had to be prepared.

Cheers! Yes, the Home Guard often seem to be overlooked, often getting only a brief mention in local history books. Many New Zealanders know that their fathers, uncles or grandfathers were members of the Home Guard but might know what that actually involved.

As a teenager I spent many holidays in Wellington exploring the various remains of the coastal defences, from those built during the Russian scare to those from the Second World War. They are great places to set the imagination racing – wondering about the ‘what if’.

Re: the German raiders, I reckon that the attacks on Nauru in December 1940 are a good example of why coastal defences were important in the Pacific – even before the Japanese entry to the war.

That story about U-862 is a classic! Thanks again.

I dug into the U-862 mythology in the 1990s. Even stripped of the hyperbole it’s an incredible tale. I was going to be interviewed on it for TV last year but the arrangement fell through.

What a wonderful insight into these brave men. Thank you so much for your detailed research and the time you have devoted to this. May I share a link to this on the Old Wellington Region Facebook page? I’m sure they’d love to read this.

Thank you very much! The time was definitely worth it – this was an important story to share. Someone else has already shared this with the Old Wellington Region FB page and they are sharing the photos with their followers. I’m hoping that someone might recognise some of the guardsmen.

Thank you, I was aware there were home guards defending NZ as after serving in ww11 my Welsh grandfather emigrated to NZ and became a home guard. He lived in Johnsonville, I scoured your photos as i knew Makara was a fav fishing shot for him and my dad, but alas, could not see him.

Those are great memories to have! Sorry that you weren’t able to spot your Dad in any of the photos – I’ve been hoping that some readers might recognise some of the guardsmen. At the least I hope that my article encourages more people to appreciate what the men and boys of the HG did.

Great story and great photos! Im especially impressed with the photos of Te Ika a Maru Bay. My family own Te Kamaru Station and we have a lot of photos from that era, but none of the Home Guard operating in the area! Fantastic – and well saved!

Of the ‘bunker at Te Ika a Maru Bay, I don’t think there are any remnants. However I will be keeping a vigilant lookout from now on.

There is a good article in papers past (Evening Post, Volume CXXXIX, Issue 147, 23 June 1945) with a couple of B&W photos of the wreck of the Tiger Moth. A very sad story indeed. There is a also a story on the incident in Missing! Aircraft Missing in New Zealand 1928 – 2000 by Chris Rudge.

Hi Micahel. It is great to hear from you! I’m glad that you found the article and photos interesting. I would’ve loved to have been able to visit Te Ika a Maru Bay during my short research trip to Makara, but unfortunately I had limited time and it was a little too far. It looks like such a beautiful area.

I’d be very curious to know if you recognise any of the buildings in the photo of the guardsmen on parade on Xmas day? I wondered if perhaps some of those structures might still be there today.

Yes, the Tiger Moth incident was very tragic. I look at it as yet another senseless loss during the war – as much as any casualties overseas.

I’ll send you an email separately – if you’d like them then I’d love to offer to send you high resolution copies of the photos from Te Ika a Maru Bay.

A great post regarding the Home Guard in Makara. Very fortunate to have photos. Very sad for the crew of the Tiger Moth ‘We Will Remember Them’. It is interesting that there are also many historic fortifications around the coast of NZ that are likely to have stories that should not be lost. I recently visited North Heads, Auckland North Shore that has great views of past America’s Cup races and Volvo Around the World Yacht Race Classic. This place is also surrounded by areas where Home Guard and Navy guarded the area from possible invasion during WWII.

Hi John, thanks for your message. Yes, there are many surviving examples of WW2 coastal fortifications up and down the country. As a teenager I spent many holidays exploring some of them around Wellington, and Godley Head at Lyttelton is another favourite spot. Unfortunately quite a few have been lost over the years due to development – many of them don’t seem to have had the protection that you’d expect for such invaluable heritage sites. Thanks for stopping by!

Was very interested to see your article in the Wellingtonian and then to read more on line. My father was Clif (only one ‘f’ – short for Wyclif) Reed. I can remember him talking about the hours they spent in the bush looking for that lost plane. I think he also produced a little book on map reading for use by the Home Guard. Thank you!

What fascinating memories to have! Thank you very much for sharing.

Hello Lemuel, Love all your photos and reading about the Home Guard in Wellington. My Dad was a conscripted into the army during WW2 and because of some medical problem, wasn’t sent overseas to fight. He was a Home Guard at Sumner in Christchurch and they had camp set up in the various caves on the coastline. I’m not sure how long he was stationed at Sumner, but I do know he was a cook at Burnham Camp and after the war ended, they wanted him to stay on in the army. My mother always said it was a shame he didn’t do this as it was a good life in the army and he was a great cook.

Thank you! Sumner would’ve been an interesting place to serve during the war, close to the approaches of Lyttelton Harbour, and with the base up at Godley Head (which is where my great great uncle was serving).

Lemuel,

You may be interested to know that the Home Guard also used old gold mines located in the hills as back up stores.

These mines were said to be equipped with a door and other fixture and fittings.

In the 1990s I was told the story and was shown by pointing an area by a local who in the 1970s approx said he was taken to one such location as a boy by his father.

I have been into that area without success and as far as we know nobody has been to the mine since. But in 2020 approx (50 years latter approx) a local having heard the story and with experience in caving geology whilst out bush bashing spotted a likely location and found the overgrown mine entrance.

I understand most of the woodwork has since decayed but the mine remains.

There are also the remnants of another mystery located on the steep escapement visible from the beach or sea below the Karaka Gully (below the old camp) which is in the form of steel work spanning a slip face – suggesting a steep track once existed across and down the face of the escarpment down to the beach below. – I did once attempt to reach it but decided due to the steep and slippery terrain caution was in order and didn’t quiet reach the steel structure.

In respect of the Tiger Moth – it was told to me by an old timer that the engine was recovered from the wreck site, and it subsequently spent quite a few years at the Makara Garage and that in fact being some years after the crash only one body (not two as the article suggests) was ever recovered. True or false I don’t know.

Thanks for that! I had read about the Home Guard’s use of mines in the area, both as caches for supplies (makes me wonder if perhaps some are waiting to be found!) and a place to hide, fighting a guerrilla war behind enemy lines. Would be curious to know what they look like.

Interesting to hear about the steel structure. Would be curious to know if that dates to the HG activity, or the fishing village, or something else. I wonder where the tiger moth engine ended up as well.

Lemuel,

Possibly there are others – I had heard stories of a hut being further up a Gully – but that would have long gone.

Not sure there would be any further undiscovered mines – it’s not that big an area but who knows ?

In respect of the Engine – I was told what happened to it (just can’t recall that story – but most likely it was a rainy day – might come in handy curiosity type project that never eventuated and I would suspect it ended up being dumped or used as weights for a mooring).

Re the tigermoths occupants – An update – reading old newspapers the story seems to be that after discovery of the wreck initially only one set of remains was found but some time latter after a larger more detailed search remains / objects were found that were connected to the 2nd body. – just to clarify the actual story beyond what I heard that only one body was found.

The steel structure is on the southwest side facing the South Island so is roughly below the army camp site / Gun emplacements so is unlikely to be related to the fishing village. – it seems to follow a possible route / track down the escarpment but being steep and made up of very loose materials appears to have mostly now frittered away and may have been a sort of railing to provide access across a scree slope closer to the beach. – Make sense that there was some sort of quick access to the beach below – with time on hands it would provide access for good swimming and plenty of sea food.

There is a Royal Signals symbol on the buildings at the top of the West Wind Farm. Meridians website claims this is an old post office but was there also a military comms presence at Makara?

Back in the late 50’s my brother’s and I located a tunnel, at the top of the hill and along a bit, just above the river mouth at Makara Beach. There was a few inches of water over the floor. Using a probing stick we walked in for about 10M, to near the end until we could not find the bottom. We concluded that there was mine shaft at that point.

John – Correct – there was a mine somewhere up there – I just can’t recall what it was – Lignite or Shale ?? perhaps – but certainly not gold nor part of the home guard.

My late father in law, George McCallum, was obviously in the Makara Battalion – he lived in Karori. I spoke to him sometimes of his experiences. He told me that they walked past the gulley where the tigermoth had crashed, but they could see no sign of it and no-one thought to explore the gulley as it seemed impossible for the plane to be hidden there. My wife, his daughter, said he spent of lot of time talking about maps after the war, and I wonder if he was in the guides, as he was a keen tramper.

I wonder if you have a photograph with him in it in your collection.

Congratulations on a great article. At present I am collecting records of military service related to my extended family, to find out what really happened to them, rather than the stories I heard and often misunderstood

Martin Reeve

Because the aircraft caught fire – In rough ground other than any fire damaged scrub etc there may have been very little visible structure remaining to indicate it was there. Even with the many station shepherds it still wasn’t found for a long time. It was reported to me that the engine was eventually recovered by locals and sat at the Makara garage for a number of years.

Hey Lemuel, My name is Max and I’m a year 13 student in Wellington New Zealand and I’m currently working on a history assessment on the New Zealand Home Guard and I’m looking for some primary sources to use for this task. I have read this article on the Home Guard and I want to find then original sources for these photos or any of the evidence you used. Also I am wondering if you had any links to any of the original sources you used whilst writing this blog, or if you know of any primary or secondary sources I could use on this topic.

Kind Regards, Max

Hi Max, a great topic for a history assessment! All images in this article with the credit “Lemuel Lyes Collection” are original wartime photographs from my personal collection. You’re more than welcome to use any of them for your assignment if you want to.

With regards to primary resources, one of the most useful ones I used was ‘RNZAF [Royal New Zealand Air Force] Accident Reports – DH 82 – NZ 1432 – Rongotai – Crashed hills, 2 dead – 23 August’ Archives New Zealand (ID: R21074874, Record No: 25/2/647). It’s the wartime accident report for the incident I mention in the article, but I also found it contained useful insights into the Home Guard exercise. It’s held in the Archives NZ Wellington office. I used quite a large number of wartime newspaper articles, all accessed through Papers Past. If you have a search on there for Makara + “Home Guard” you should find them. Another useful source I used was an article called “The Makara Guerrillas” by Greville Wings, in “The Stockade” No. 29. 1996 – The Karori Historical Society. The Wellington Public Library has a copy of that. I hope that helps you, and best of luck with the assignment!

Thank you so much for the help, those are exactly what I have been looking for!

Kind regards Max